Quickstart

This page provides an example of how to perform a single VPLanet simulation. It

introduces you to the

input and output files, executing the simulation, and visualizing the result with

vplot. This example,

however, only represents a small fraction of the VPLanet use cases, so it is

intended to be representative of how

to use the code. In other words, the files shown below represent the typical

structure, formatting and syntax for all VPLanet simulations.

Understanding this example will enable you to build off the other examples included in this repository.

Physics of the Example

Let’s go over how to use VPLanet by simulating the evolution of

water on Venus. Isotopic evidence

suggests Venus may have had a similar amount of water to Earth in the

past (Donahue et al., 1982),

but because of vigorous hydrodynamic escape it may have lost all of it in the

first few hundred Myr (Hunten, 1973).

Here we’re going to use the stellar

and atmesc modules of VPLanet to jointly model the evolution

of the Sun and Venus in order to estimate how long it took for Venus to lose all

its surface water.

Note

This guide shows how to interpret the VenusWaterLoss example, but here we will only include one planet, whereas the example uses three. Modifying that example to match the input files shown below will generate the figure at the end of this guide.

The basic workflow for a VPLanet simulation is to 1) create input

files with the relevant system, star, and/or planet parameters, 2) execute

VPLanet directly from the command line, and 3) interpret the ASCII text

output generated in a log file and/or time-series data file.

The Input Files

VPLanet takes 1 file as input, which contains “options” that direct the

execution of the code. Each option is defined by a single, case-sensitive name,

and is followed by one or more arguments. The option file included in the command

line is called the “primary input file” and provides

VPLanet with the most general information about the simulation, e.g.

the integration method, the stop time, what bodies are in the system, etc. It

also must include a list of files that contains information about the bodies in

the system, called the “body files.”

This primary input file is usually called vpl.in, but you can call it

whatever you’d like. We’ll start by presenting an example, and then dissect it

after. The primary input file generally takes a form like this:

vpl.in

1# General Options

2sSystemName solarsystem # System Name

3iVerbose 5 # Verbosity level

4bOverwrite 1 # Allow file overwrites?

5saBodyFiles sun.in $ # List of all bodies files for the system

6 venus.in # The $ tells VPLanet to continue to the next line

7

8# Input/Output Units

9sUnitMass solar # Options: gram, kg, Earth, Neptune, Jupiter, solar

10sUnitLength AU # Options: cm, m, km, Earth, Jupiter, solar, AU

11sUnitTime YEARS # Options: sec, day, year, Myr, Gyr

12sUnitAngle d # Options: deg, rad

13

14# Input/Output

15bDoLog 1 # Write a log file?

16iDigits 6 # Maximum number of digits to right of decimal

17

18# Evolution Parameters

19bDoForward 1 # Perform a forward evolution?

20bVarDt 1 # Use variable timestepping?

21dEta 0.01 # Coefficient for variable timestepping

22dStopTime 4.6e9 # Stop time for evolution

23dOutputTime 1e6 # Output interval for forward files

Note

You can obtain descriptions of the options from the command line with the

-h (short help) or -H (long help) flags. You can also search

the options here.

As described above, the options are specified with a unique string (e.g.,

dEta or dStopTime) followed by white space and then the value(s)

for the option. Note that the leading lower case letter(s) of each option’s name

describes the type (or “cast”) of the expected argument: b = Boolean, i = integer,

d = double precision, s = string. If an “a” follows one of these letters, then

the argument may contain multiple values, i.e. may be an “array,” e.g.

saBodyFiles on line 5. Only one option is allowed per line.

The order of the options is irrelevant, and white space is ignored. Comments

can be specified anywhere with the hashtag (#) symbol. Note that array options

can span multiple lines with the $ symbol, as shown in the arguments to

saBodyFiles. The $ tells VPLanet to find the next member of the

array on the next line. The # and $` symbols are the only special characters in

VPLanet input files.

The name of each option is intended to be helpful, i.e. self-explanatory, but

here’s a

line-by-line breakdown to be clear (ignoring comments and white space): We’re

calling the system "solarsystem", which automatically sets the names of

output files to use the argument as the prefix, as well as enable vplot

to easily use the name. We specified maximum verbosity (5),

so VPLanet will talk a LOT. We’re allowing output file overwrites.

Next we get to the all important list of body files, and we’re telling the code to expect

two that are called sun.in and venus.in, which we’ll describe

below. (Note that in the

VenusWaterLoss example, three planets are

simulated, each representing a different amount of initial water content.)

Next, we set the default units for I/O: solar masses, astronomical units, years,

and degrees. Because we set them in the primary input file, the choices are

propagated to the body files, but a user can specify units for each body. In the

case of some double precision options, the user can also force specific units

with a negative sign, as described below.

Next, bDoLog tells the code to generate a log file; iDigits sets the

output precision to 6 decimal places. The last block of options tells VPLanet

how to simulate the system. We want to evolve the system forward in time. We will employ

variable (adaptive) timestepping with, as set in the next line, the accuracy

coefficent dEta set to 0.01, i.e. the code will set the time step to be 100

times shorter than the time required for the value of the fastest changing

variable to change by a factor of 2. The final two lines specify the length of

the integation (in units of sUnitTime), and the frequency of outputs.

Note

The smaller the value of dEta, the higher the precision of the integration, but

the slower it will run. We have found that many cases converge for a

value of 0.01, but some require 0.0001. Always test for convergence before

assuming VPLanet output is accurate.

With the primary input file completed, let’s now turn to the two body files,

sun.in and venus.in.

sun.in

1# Star's Parameters

2sName sun # Body's name

3saModules stellar # Modules to apply, exact spelling required

4

5# Physical Parameters

6dMass 1.00 # Mass of the star in solar masses

7dAge 5e7 # Age in years at integration start

8

9# STELLAR Parameters

10sStellarModel baraffe # Stellar evolution model: `baraffe` or `none`

11dSatXUVFrac 1.e-3 # XUV luminosity fractional saturation level

12dSatXUVTime 1e8 # XUV saturation timescale in years

13

14# These are the parameters that vplanet will output as arrays in the

15# `.forward` or `.backward` evolution files. Run `vplanet -h` for a list

16# of all options. Note that the "-"" sign creates output with custom units.

17saOutputOrder Time -LXUVStellar

As before, the parameter names are intended to be self-explanatory. Note that we’re only

setting a few, and those that are not specified assume their default values.

Here we have a few differences with VenusWaterLoss:

That example assigns a hexadecimal color that can be used for plotting with vplot, and

uses the negative option for dSatXUVTime, which means the units are Gyr. For this

guide, we’re running a shorter integration.

We gave the star a name and

told VPLanet we want to use the stellar module to compute

its evolution. We assigned its mass and age at simulation time = 0, and

set a few stellar-specific properties. We’ll use the

Baraffe et al. (2015)

evolutionary tracks and the Ribas et al.

(2005) XUV

evolution power law with a saturation fraction of 0.001 and saturation time of

100 Myr. Note that “time” is different than

“age” in that the former is the internal counter for the simulation,

whereas the latter is the physical age of the star since some birth time. For a

compete description of the physics in VPLanet, please consult the manual.

The option saModules is of particular importance in the body files as it sets the physical models (“modules”) to be applied to the body. In this case, the only module is “stellar”, or the quiescent evolution of a star from formation to the end of the hydrogen burning. In more complicated simulations, multiple modules can be added to the argument list and the code will automatically add the new equations, including coupling of any parameters that are affected by multiple modules.

Another important VPLanet option is saOutputOrder, which is a list

of all parameters to be output during the integration at a cadence defined by

dOutputTime (see vpl.in, line 23).

In this case we requested two “outputs”: time and XUV luminosity. (The example

includes a few more parameters.) Output names need only

be unique, unlike the option names, but it’s often easier to understand the

output if the full name is provided. As shown below, the log file contains the

list of outputs and their units for each body.

Note

Some output parameters (usually those that are positive-definite) can be prepended with a minus sign to force the output into a customized unit. This information can also be found in the help file. In general these “custom units” are tailored to the Sun-Earth system.

Next up is the input file for the planet, Venus. This example is based off venus1.in in VenusWaterLoss.

venus.in

1# Planet's Parameters

2sName venus # Body's name

3saModules atmesc # Modules to apply, exact spelling required

4saOutputOrder Time $

5 -SurfWaterMass $

6 -OxygenMantleMass

7

8# Physical Parameters

9dMass -0.815 # Here, the - symbol means Earth masses

10dRadius -0.9499 # Here, the - symbol means Earth radii

11dSemi 0.723 # Semi-major axis

12dEcc 0.006772 # Eccentricity

13

14# ATMESC Parameters

15dSurfWaterMass -1.0 # Initial surface water in Earth oceans

16sWaterLossModel lbexact # Water loss model; Luger and Barnes (2015)

17bInstantO2Sink 1 # O2 is absorbed instantly at the surface

18sAtmXAbsEffH2OModel bolmont16 # XUV absorption efficiency model

This file looks pretty similar to the previous one, but it’s worth noting

a few things. First, we appear to have given the planet a negative

mass and radius! As mentioned above, the negative sign is actually

telling

VPLanet to apply different units. Many

parameters have an associated customized unit that overrides the default units

specified in vpl.in. In this case, dMass and dRadius have customized units

of Earth masses and Earth radii, respectively, so we’re OK.

Similarly, note that two outputs have a negative sign in front of them. These

symbols tell VPlanet to output to this parameter to the data files in

custom units.

Finally, we set some atmesc-specific parameters. We told the code

to initialize the planet with one Earth ocean’s worth of water (the minus sign, again, indicates

custom units) and to compute the water loss using the model

from Luger and Barnes (2015)

and oxygen be absorbed at the surface instantly. The sWaterLossModel

employs the XUV absorption efficiency model from Bolmont et al. (2016).

Running the Code

Now that you understand how the input files work, we are ready to run the code!

vplanet vpl.in

Upon running this command in a terminal, you may see all sorts of messages printed to the screen:

INFO: sUnitMass set in vpl.in, all bodies will use this unit.

INFO: sUnitTime set in vpl.in, all bodies will use this unit.

INFO: sUnitAngle set in vpl.in, all bodies will use this unit.

INFO: sUnitLength set in vpl.in, all bodies will use this unit.

INFO: sUnitTemp not set in file sun.in, defaulting to Kelvin.

INFO: sUnitTemp not set in file venus1.in, defaulting to kelvin.

INFO: sUnitTemp not set in file venus2.in, defaulting to kelvin.

INFO: sUnitTemp not set in file venus3.in, defaulting to kelvin.

INFO: dRotPeriod < 0 in file sun.in, units assumed to be Days.

INFO: dMass < 0 in file venus.in, units assumed to be Earth masses.

INFO: dSemi < 0 in file venus.in, units assumed to be AU.

INFO: dRadius < 0 in file venus.in, units assumed to be Earth radii.

INFO: dRotPeriod < 0 in file venus.in, units assumed to be Days.

INFO: dSurfWaterMass < 0 in file venus.in, units assumed to be Terrestrial Oceans (TO).

INFO: dMinSurfWaterMass < 0 in file venus.in, units assumed to be Terrestrial Oceans (TO).

INFO: dJeansTime not set for body venus, defaulting to 3.16e+16 seconds.

Input files read.

INFO: Age set in one file, all bodies will have this age.

INFO: sOutFile not set, defaulting to solarsystem.sun.forward.

INFO: sOutFile not set, defaulting to solarsystem.venus.forward.

INFO: sIntegrationMethod not set, defaulting to Runge-Kutta4.

INFO: dEnvelopeMass < dMinEnvelopeMass. No envelope evolution will be included.

INFO: dEnvelopeMass < dMinEnvelopeMass. No envelope evolution will be included.

INFO: dEnvelopeMass < dMinEnvelopeMass. No envelope evolution will be included.

INFO: Radius of Gyration set for body 0, but this value will be computed from the grid.

All of sun's modules verified.

All of venus's modules verified.

Input files verified.

Log file written.

You can safely ignore most of this output: VPLanet is just being very

verbose (as requested!) about what it’s doing. It is, however, a good

idea to examine those messages to ensure you haven’t made any mistakes! If

VPLanet thinks you’re doing something dubious,

it will output a WARNING and you should take care that you are comfortable with

your options. VPLanet will also ERROR in cases of incompatible options,

values out of bounds, etc., and provide the file and line number(s)

that contain the issue(s). Note that if you did run the examples/VenusWaterLoss

case you will see more Venuses in the output.

Anfter informing you of many of the decisions VPLanet made,

things will go silent for a couple seconds, and then you’ll see:

Evolution completed.

Log file updated.

Simulation completed.

The code is done running, and you should see several output files in the current directory.

The Output Files

The log file records the details of the simulation and captures a snapshot of the system at the initial step and the final step of the evolution. Here’s a very condensed version of what you should see:

solarsystem.log

Executable: vplanet

Version: <GITVERSION>

System Name: solarsystem

Primary Input File: vpl.in

Body File #1: sun.in

...

---- INITIAL SYSTEM PROPERTIES ----

(Age) System Age [sec]: 1.577880e+15

(Time) Simulation Time [sec]: 0.000000

...

----- BODY: sun ----

Active Modules: STELLAR

(Mass) Mass [kg]: 1.988416e+30

...

----- STELLAR PARAMETERS (sun)------

(LXUVStellar) Base X-ray/XUV Luminosity [LSUN]: 0.000677

Output Order: Time[year] LXUVStellar[LSUN]

----- BODY: venus ----

Active Modules: ATMESC

(Mass) Mass [kg]: 4.867332e+24

...

----- ATMESC PARAMETERS (venus)------

(SurfWaterMass) Surface Water Mass [TO]: 1.000000

...

Output Order: Time[year] SurfWaterMass[TO] OxygenMantleMass[bars]

---- FINAL SYSTEM PROPERTIES ----

(Age) System Age [sec]: 1.467428e+17

(Time) Simulation Time [sec]: 1.451650e+17

...

----- BODY: sun ----

Active Modules: STELLAR

(Mass) Mass [kg]: 1.988416e+30

...

----- STELLAR PARAMETERS (sun)------

(LXUVFrac) X-ray/XUV Luminosity Fraction []: 8.892684e-06

...

----- BODY: venus ----

Active Modules: ATMESC

(Mass) Mass [kg]: 4.867332e+24

----- ATMESC PARAMETERS (venus)------

(SurfWaterMass) Surface Water Mass [TO]: 0.000000

(OxygenMantleMass) Mass of Oxygen in Mantle [bars]: 199.365415

...

The log file lists parameter values in system units: SI. This choice allows users to be sure that all the calculations will proceed correctly. Note, however, that any output given a negative sign prefix will appear in the custom units. Also note that the log file contains the complete initial and final conditions for all outputs for the selected modules. The first word in many of the log file lines is in parentheses, which indicates the parameter can be supplied to saOutputOrder to record the evolution over time.

Next, we will consider the output files, one per body, which are often called “forward

files” or “backwards files”. The

columns in these files correspond to names in the saOutputOrder

option in the corresponding input files. Recall that for the

Sun, we requested that VPLanet output the simulation time

and the XUV luminosity (in solar units since we used the minus sign):

solarsystem.sun.forward

0.000000 0.000677

1.000000e+06 0.000677

2.000000e+06 0.000678

3.000000e+06 0.000678

4.000000e+06 0.000678

...

Currently forward files do not include headers, but you can verify the outputs columns and their units in the log file. For the planet, we asked for the time, the amount of surface water (with a minus sign, indicating in units of Earth oceans), and the amount of oxygen absorbed by the mantle (with a minus sign, indicating units of bars):

solarsystem.venus.forward

0.000000 1.000000 0.000000

1.000000e+06 0.978763 4.238860

2.000000e+06 0.957524 8.477719

3.000000e+06 0.936283 12.716579

4.000000e+06 0.915044 16.955439

...

Plotting

With the output generated, it is often convenient to plot the output. While any plotting

package can be used, the VPLanet team has created a customized tool that enables

both fast plotting of output, as well as tools to generate publication worthy figures.

The vplot tool (docs here)

can be used to easily visualize the results of

any VPLanet simulation. After VPLanet finishes, simply run

vplot

for the a plot like the following to appear:

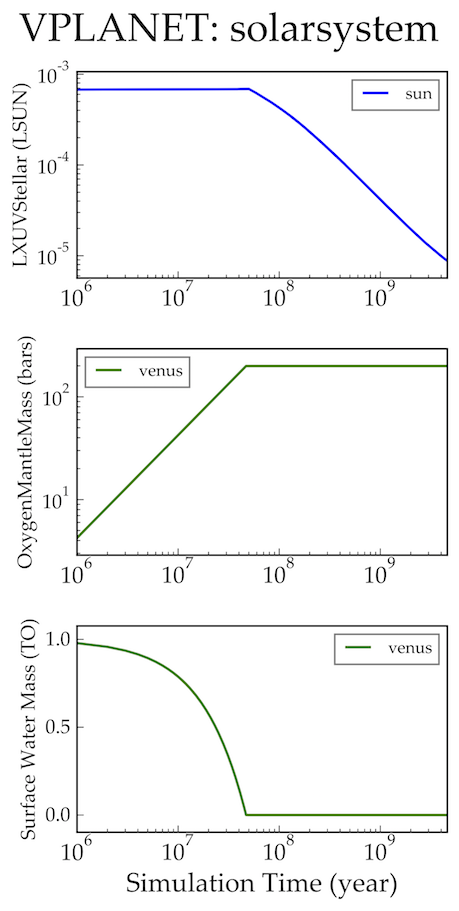

vplot plots the time series of all the variables from all the bodies

in a single figure. Here we see the evolution of the stellar XUV emission, which declines

dramatically after the saturation timescale ends (top); the increase

in the amount of oxygen in the planet’s mantle, which is absorbed from

the oxygen released from the photolysis of water (center); and

the desiccation of the planet’s surface, caused by the hydrodynamic escape of

hydrogen to space. In this simulation, Venus loses all of its surface water

in about 50 Myr.

Next Steps

The above example describes one use case, but VPLanet can simulate many

more phenomena, all with the same executable and input file format. Navigate to

the examples directory to see the physics that are currently available. Each example provides instructions on how

to generate output and a figure.

Also available are Python scripts for generating parameter sweeps and storing the data from those sweeps. See the parameter sweep guide for more details.